This page discusses some general aspects of the Interment, the Enemy Alien Act, Martial Law, and habeas corpus. Each section includes a brief summary followed by a more detailed discussion including case cites. Other pages discuss Japanese American Legal History (General) and Japanese American Legal History (The Internment).

E.O. 9066 Internments

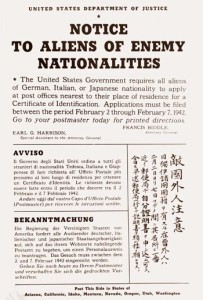

Summary: Japanese Americans were not the only citizens subject to Executive Order 9066. Citizens of German and Italian descent were also subject to the E.O. 9066 exclusions, though were generally afforded individual “loyalty hearings” and were not excluded as a class based on race. When such individuals sued in court to reverse their exclusions, the courts generally undertook a probing analysis, without deference to the government’s argument of “military necessity.”

Summary: Japanese Americans were not the only citizens subject to Executive Order 9066. Citizens of German and Italian descent were also subject to the E.O. 9066 exclusions, though were generally afforded individual “loyalty hearings” and were not excluded as a class based on race. When such individuals sued in court to reverse their exclusions, the courts generally undertook a probing analysis, without deference to the government’s argument of “military necessity.”

Discussion: In addition to the mass race-based exclusions of the Japanese Americans pursuant to Executive Order 9066, various German Americans and Italian Americans were also subject to exclusion (on an individual basis, at least, insofar as there was no massive race-based exclusion) from the “military areas.” Such individuals were apparently, generally, allowed a hearing before a military tribunal before the “Individual Exclusion Order” was issued. In theory, they were rounded up “for cause,” but the “cause” was often less than rock-solid. See, generally, Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Washington DC 1982), Civil Liberties Public Education Fund/University of Washington Press 51-60 (1997); See also, Jacobs v. Barr, 959 F.2d 313 (D.C. Cir. 1992), vacated, 482 U.S. 64 (1987), Ebel v. Drum, 52 F.Supp. 189 (D. Mass. 1943); Schueller v. Drum, 51 F.Supp. 383 (E.D. Pa. 1943), United States v. Meyer, 140 F.2d 652 (2d. Cir. 1944), Wilcox v. DeWitt, 71 F.Supp. 704 (S.D. Ca. 1943), Wilcox v. Emmons, 67 F.Supp. 339 (S.D. Cal. 1946), Von Knorr v. Miles, 60 F.Supp. 962 (D. Mass. 1945).

The remarkable willingness of the Supreme Court to defer to the military’s estimation of “military necessity” in Hirabayashi and Korematsu stands in sharp contrast to the procedures used when “Individual Exclusion Orders” of German Americans were at issue.

For example, in Ebel v. Drum, 52 F.Supp. 189 (D. Mass. 1943)(decided after Hirabayashi, but before Korematsu), the court struck down an “Individual Exclusion Order” issued against Mr. Ebel, on the grounds that “the war power does not remove limitations safeguarding essential liberties.”

General Drum, Military Commander of the East Coast Military Command, had declared Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, parts of Florida, and the District of Columbia to be a military area under Executive Order 9066.

Mr. Ebel, a naturalized citizen, was afforded an administrative hearing before the Individual Exclusion Order was issued against him, on the grounds of “military necessity.” He appealed to the federal district court. At the trial, the court independently determined that Ebel’s parents and children resided in Germany; that he had a son who was serving in the German military; that another son, living in the United States had refused to serve against Germany; that he had attended various functions at the German consulate; and that he was President of the Kyffhaueser Bund, Boston Branch, for 2 or 3 years, concluding in January 1942. The Bund was a pro-Nazi organization “in its encouragement of the military spirit and keeping alive the love of Germany in the hearts of former German soldiers and civilians.”

The court noted that “[i]f there was an appropriate exercise of war power, the validity of the exclusion order is not impaired because it is restrictive of the citizen’s liberty.” However, the court continued, such a power cannot be exercised “except in case of military necessity or emergency, and the question whether such military necessity existed is subject to judicial review.”

Similarly, in Schueller v. Drum, 51 F.Supp. 383 (E.D. Pa. 1943), Ms. Schueller appealed the Hearing Board’s imposition of an exclusion order against her. The court struck it down, stating that “Congress cannot authorize the executive to establish by conclusive proclamation the very thing which, upon familiar principle, would have been the subject of judicial scrutiny.”

Admittedly, Schueller and Ebel were decided before Korematsu and the district courts probably did not think that the reasoning in Hirabayashi applicable to a mere curfew was appropriate to an exclusion. Other courts, however, were willing to follow the Hirabayashi court and almost unequivocally defer to the military’s judgment. See, Wilcox v. DeWitt, 71 F.Supp. 704 (S.D. Cal. 1943).

Enemy Alien Act

Summary: Under the Enemy Alien Act, the government has the power to incarcerate nationals of nations with whom the United States is at war. This power was used against German, Italian and Japanese nationals resident in the United States during World War II.

In addition, it was used against naturalized American citizens, after citizenship was stripped for apparently un-American associations. Further, it was used against Latin American of German, Japanese and Italian descent who were deported from their own countries to the United States.

Discussion: In addition to the power to establish military areas and exclude enemy aliens and citizens therefrom (pursuant to Executive Order 9066 and its implementing legislation), the government has the power under the Enemy Alien Act to deal with enemy aliens by permitting them to be “apprehended, restrained, secured and removed [from the United States]” if they otherwise “refuse or neglect” to depart. 50 U.S.C. S21. (Generally, it seems, such individuals were then exchanged for U.S. civilians resident in the enemy nations). Pursuant to this power, various German enemy aliens (also Japanese and Italians, but the Germans seem to be the only ones who sued) were rounded up and held in internment camps for eventual expulsion from the United States. Schwarzkopf v. Watkins, 137 F.2d 808 (2d Cir. 1943); Zeller v. Watkins, 167 F.2d 279 (2d Cir. 1943); Citizens Protective League v. Clark, 155 F.2d 290 (D.C. Cir. 1946); Von Heymann v. Watkins, 159 F.2d 650 (2d. Cir. 1947);.Jaegeler v. Carusi, 342 U.S. 347 (1952). On its face, such programs seem to comport with both the Constitution and international law.

However, the law was also applied to some naturalized citizens and some Latin Americans (of Japanese, German or Italian ancestry):

Latin American Enemy Aliens

The United States expanded the internment program to include about 3000 deportees of German, Italian and Japanese ancestry from Latin America. About two thirds were of Japanese ancestry; about 80 percent were from Peru. At the recommendation of the U.S. government, the Latin American countries sent their enemy aliens to the United States for safe-keeping and hostage exchange.

If the deportees were citizens of the enemy nations, the Enemy Alien Act was used to incarcerate them, in theory only until their departure from the United States could be arranged. See, Von Heymann v. Watkins, 159 F.2d 650 (2d. Cir. 1947). If the deportees were citizens of the respective Latin American countries, in certain instances, they were stripped of their citizenship upon their deportation to the United States. The U.S. government interned these individuals on the basis that they were enemy aliens (on the theory that they reverted to Japanese, German or Italian citizenship). The courts eventually rejected this argument. Steinvorth v. Watkins, 159 F.2d 50 (2d. Cir. 1947).

De-Naturalization

In certain instances, the Enemy Alien Act was applied against persons who were stripped of their (naturalized) American citizenships and then, no longer being Americans, treated as enemy aliens. (A native-born citizen can only lose citizenship through act of treason or felony. Knauer v. United States, 328 U.S. 654 (1946)(Rutledge, dissenting)).

Under the Naturalization Act, individuals wishing to become citizens must file a petition representing that they are attached to the principles of the Constitution, and also swear an oath of allegiance to the United States. If the petitioner fraudulently asserts his attachment to the principles of the Constitution or swears the oath falsely, his citizenship can be stripped away. Baumgartner v. United States, 322 U.S. 665 (1944); Schneiderman v. United States, 320 U.S. 118 (1943); United States v. Haas, 51 F.Supp. 910 (N.D.N.Y. 1943).

The Supreme Court approved this practice, Knauer v. United States, 328 U.S. 654 (1946), though the dissent argued that the consequence was that naturalized citizens thereby had a “second-class” citizenship. For example, in Knauer, Mr. Knauer became a citizen in 1937. He, apparently, approved of Adolf HItler and solicited funds for the German Winter Relief Fund, for which German consulates solicited money in the United States. He was also (apparently) a member of the German-American Bund, which “advocated the Nazi philosophy” of “racial superiority,” the “Pan-German state,” and Lebensraum. In addition, Mr. Knauer was a founder of the pro-Nazi German American Citizens Alliance, which was formed to compete with the Federation of German American Societies (which represented various German America associations), which had refused to recognize the swastika as the flag of the German Reich. In addition, he conducted various other activities through which the Court concluded he had sworn falsely and fraudulently executed his petition.

The Court’s majority denied it was creating “second-class” citizenship, and did indicate that the standard of proof required was strict. It even re-examined the facts, without regarding the opinions of the lower courts as conclusive. As the Court stated, [g]reat tolerance and caution are necessary lest good faith exercise of the rights of citizenship be turned against the naturalized citizen and be used to deprive him of the cherished status.” Moreover, the Court stated, “[w]ere the law otherwise, valuable rights would rest upon a slender reed, and the security of our status of our naturalized citizens might depend in considerable degree upon the political temper of majority thought and the stresses of the times.”

The dissenting opinion, while conceding that Mr. Knauer was “a thorough-going Nazi, addicted to philosophies altogether hostile to the democratic framework in which we believe and live,” noted that “if one man’s citizenship can thus be taken away, so can that of any other.” Knauer v. United States, 328 U.S. 654 (1946)(Rutledge, dissenting). Rutledge argued that “[u]nless it is the law that there are two classes of citizens, one superior, the other inferior, the status of no citizen can be annulled for causes or by procedures not applicable to all others. To say that Congress can disregard this fact and create inequalities of status as between a native and foreign-born citizens by attaching conditions to their admission, to be applied retroactively after that event, is only to say in other words that Congress by using that method can create different, and inferior, classes of citizenship.”

He concluded, “if [by prohibiting the stripping of citizenship under these circumstances] some or even many disloyal foreign-born citizens cannot be deported, it is better so that to place so many loyal citizens in inferior status. And there are other effective methods for dealing with those who are disloyal, just as there are for such citizens by birth.”

Post-Script

The Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit rejected a German American’s claim that the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was unconstitutional, since only citizens and enemy aliens of Japanese ancestry were eligible for redress. Jacobs v. Barr, 959 F.2d 313 (D.C. Cir. 1992), vacated, 482 U.S. 64 (1987). Mr. Jacobs had argued that since the Act singled out for special treatment Japanese Americans as well as Japanese “enemy aliens,” it improperly discriminated against Italian Americans, German Americans, and German and Italian enemy aliens. Mr. Jacobs was the child of an internee and thus an American citizen.

In the mid-90′s, a class action lawsuit was filed against the government on behalf of those aliens who were interned in the United States from Latin America. See, Mochizuki v. United States. I believe the class was limited solely to internees of Japanese ancestry. The government settled the case in mid-August 1998.

Senator Alfonse D’Amato was a co-sponsor of a bill to apologize to Italian Americans for their internment during the war.

Martial Law and Habeas Corpus

Summary: The military government in Hawaii imposed martial law and suspended the writ of habeas corpus during World War II. Thus, the power of the military to intern civilians was presumably greater there than on the mainland. Nevertheless, no mass exclusions were imposed. Moreover, when martial law was challenged, in Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304 (1946), the Supreme Court announced that (certain) constitutional guarantees must be preserved even in the face of military necessity. On its face, the Supreme Court’s holding cannot be reconciled with Korematsu, and may, in fact, constitute a partial repudiation of Korematsu. However, until another internment arises which may be challenged in court, Korematsu remains the law of the land and valid Supreme Court precedent.

Discussion: “The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” U.S. Const., Art. I, s. 9, cl. 2.

The writ of habeas corpus (Latin for “you have the body”), enshrined in the Constitution, is essentially a mechanism whereby persons may challenge an unlawful imprisonment. That is, those held by the government must be brought before a court and have charges leveled against them or released (the theory being that, if you are being unlawfully detained, a court will not aid in that detention).

If habeas corpus had been lawfully suspended during World War II, the internment of citizens based on race may have been constitutional on that basis alone. For example, Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus during the Civil War. Ex parte Milligan, 4 Wall. 2 (1866). However, in contrast to its holdings in Hirabayashi and Korematsu, the Supreme Court indicated that the imposition of martial law does not necessarily vitiate protections inherent in the Bill of Rights:

Martial law was declared in Hawaii during World War II, and habeas corpus was suspended there. Thus, the power of the military to round up civilians in Hawaii was presumably greater than on the mainland, where habeas corpus remained available. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court’s examination (after the war) of the internment and exclusion in Hirabayashi and Korematsu was considerably less searching than its analysis of the imposition of martial law in Hawaii (in the context of a civilian’s right to trial by jury vs. trial by military tribunal, and whether a writ of habeas corpus should be granted).

Even when martial law is imposed, the Court declared, constitutional rights must be respected. Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304 (1946)(“The right to jury trial and the other constitutional rights of an accused individual are too fundamental to be sacrificed merely through a reasonable fear of military assault.”). In striking down the military government’s closure of the civil courts, the Supreme Court noted that “[f]rom time immemorial despots have used real or imagined threats to the public welfare as an excuse for needlessly abrogating human rights.” (Incidentally, the Kahanamoku in the case caption is the swimmer-surfer Duke Kahanamoku who, at the time, was a military police office who arrested Duncan for public drunkenness.)

The Duncan Court further rejected the argument that “persons of Japanese descent. . . are of such doubtful loyalty as a group to constitute a menace justifying the denial of the procedural rights of all accused persons in Hawaii.” The Court noted that “there have been no recorded acts of sabotage, espionage or fifth column activities by persons of Japanese descent either on or subsequent to December 7, 1941.”

The Court admonished that “[e]specially deplorable, however, is this use of the iniquitous doctrine of racism to justify the imposition of military trials. Racism has no place whatever in our civilization. The Constitution as well as the conscience of mankind disclaims its use for any purpose, military or otherwise. It can only result, as it does in this instance, in striking down individual rights and in aggravating rather than solving the problems toward which it is directed. It renders impotent the ideal of the dignity of the human personality, destroying something of what is noble in our way of life. We must therefore reject it completely whenever it arises in the course of a legal proceeding.”

The Korematsu and Duncan decisions cannot readily be reconciled, because they seem to imply that civilians under a regime of martial law (i.e., where there is a threat of invasion sufficient to render the inefficiencies of civil government unwise) are to be granted more rights (i.e., the courts will not defer to the military), than when martial law is not declared (the civil government still being capable of functioning), but the civil government nevertheless imposes equivalent restrictions upon civil liberties. Of course, one may optimistically conclude from Duncan that the Court has rejected the sort of discriminatory practice it approved in Korematsu; but since the issue of exclusion was not before the Court the legality of the relocation remains good law.