Although much ink and many pixels have been used to discuss the Japanese American internment, there doesn’t seem to be all that much reflecting the legal regime that affected Japanese Americans outside the period from 1942-1945. This section provides a general overview, including discussions of Naturalization, Alien Land Laws, Miscegenation Laws, and “Separate but Equal.” Other pages discuss Japanese American Legal History (The Internment) and Japanese American Legal History (Enemy Aliens and Habeas Corpus).

Naturalization

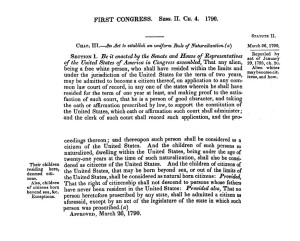

The original Naturalization Act of 1790 provided that “[a]ny alien being a free white person. . . may be admitted to become a citizen. . .” This was amended in 1870 after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution to provide that naturalization was permitted only of “aliens, being free white persons and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent.” Others were referred to as “aliens ineligible to citizenship.”

The original Naturalization Act of 1790 provided that “[a]ny alien being a free white person. . . may be admitted to become a citizen. . .” This was amended in 1870 after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution to provide that naturalization was permitted only of “aliens, being free white persons and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent.” Others were referred to as “aliens ineligible to citizenship.”

The first Japanese immigrants arrived in the United States in the late 1800′s. The issue then, of course, became whether the issei, or immigrant generation, was eligible to become citizens (their children, born in the United States, were eligible and, in fact, automatically became citizens). After a variety of state court cases and lower federal court cases, the United States Supreme Court entertained the question in 1922. In Ozawa v. United States, 260 U.S. 178 (1922) (and its companion case, Yamashita v. Hinkle, 260 U.S. 199 (1922)), the Supreme Court announced that the issei were not eligible to citizenship, since “white persons” referred solely to “a person of the Caucasian race.”

Several years later, in rejecting the argument that Asian Indians could become naturalized citizens, the Supreme Court decided that the terms “Caucasian” and “white persons” were not completely synonymous. In United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, 261 U.S. 204 (1923), the Court noted that “Caucasian” can refer to “the Hindu” (apparently the term in common usage at the time for Asian Indians), various Polynesians, as well as “the Hamites of Africa.” The Court then determined that “white persons” ought to be interpreted within the “general understanding” rather than that of ethnologists.

The Court denied that it was suggesting the “slightest question of racial superiority.” Instead, the Court said, “what we suggest is merely racial difference and it is of such character and extent that the great body of our people instinctively recognize it and reject the thought of assimilation [of 'asiatic peoples'].” The Court further noted that, while “children of English, French, German, Italian, Scandinavian and other European parentage quickly merge into the mass of our population and lose the distinctive hallmarks of their European origin . . . it cannot be doubted that the children born in this country of Hindu parents would retain indefinitely the clear evidence of their ancestry.”

In 1924, the Congress passed the Exclusion Act (8 U.S.C. §213[c]), which halted immigration from Japan altogether.

The prohibitions against naturalization of those not white or black generally held against all Asian immigrants, at least until World War II. During that time, Asian Indians and Chinese were allowed to become citizens. The general proscription against Japanese immigrants from becoming citizens, however, was not repealed until 1952.

Alien Land Laws

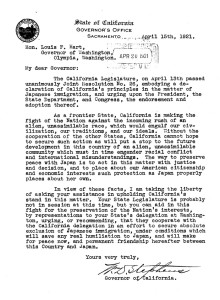

It was in this context that the State of California passed, in 1913 and later, by voter initiative in 1920, the first of a series of “Alien Land Laws.” Pursuant to such laws, those “ineligible to citizenship” (i.e., Asian immigrants) were not allowed to own or lease “real property” (i.e., land) unless a United States treaty provided otherwise. The consequence was that Japanese immigrants were not allowed to own farms in California. Most of the states west of the Mississippi River enacted similar laws soon after.

According to these laws, if an alien not eligible to citizenship tried to lease or own agricultural land, the deal was considered null and the land escheated, that is, became the property of the State. The constitutionality of the Alien Land Laws was upheld by the United States Supreme Court in the 1920′s. See, Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197, 44 S.Ct. 15 (1923); Porterfield v. Webb, 263 U.S. 225, 44 S.Ct. 21 (1923); Webb v. O’Brien, 263 U.S. 313, 44 S.Ct. 112 (1923); Frick v. Webb, 263 U.S. 326, 44 S.Ct. 115 (1923); Cockrill v. California, 268 U.S. 258, 45 S.Ct. 490 (1925)

The Alien Land Laws were justified as a means of protecting white farmers. As the California Attorney General stated, “the American farm. . .cannot exist in competition with a farm developed by Orientals…” See, Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948), quoting brief in Porterfield v. Webb, 263 U.S. 225, 44 S.Ct. 21 (1923).

However, during legislative debate on the bill, one of the California assemblymen stated “I would rather every foot of California was in its native wilderness that to be cursed by the foot of these yellow invaders, who are a curse to the country, a menace to our institutions, and destructive of every principle of Americanism. I want no aliens, white, red, black or yellow, to own a foot of land in the state of California.” Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 n. 4 (1948). Another assemblyman said that he “intensely and unalterably hated the Japanese, whom he characterized as a ‘bandy-legged bugaboo, miserable craven Simian, degenerated rotten little devil.’” Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 n. 4 (1948)(citation omitted).

One way around these laws was for the issei parent to purchase the land for their children; however, most states closed these loopholes, holding that a minor’s property could not be held in trust by an alien ineligible to citizenship. Some states even forbade a citizen spouse from owning land and allowing their spouse (husbands, usually) to farm or go upon the land.

The constitutionality of these statutes was upheld until after World War II. In 1948, in the Oyama case and in Takahashi v. Fish & Game Comm’n., 334 U.S. 410, 68 S.Ct. 1138 (1948), the United States Supreme Court struck down various procedural aspects of the Alien Land Laws (though not their “main” provisions). The Supreme Court of Oregon found that state’s Alien Land Law to be unconstitutional in 1949. See, Namba v. McCourt, 185 Ore. 579, 204 P.2d 569 (1948). The California Supreme Court struck down the California Alien Land Law in 1952. Fuji v. California, 38 Cal.2d 718, 242 P.2d 617 (1952).

Miscegenation Laws

After the Reconstruction period following the Civil War, most of the states passed “anti-miscegenation laws” which forbade marriages between “whites” and “non-whites.” In 1952, twenty-nine of the (then) forty-eight states had such laws: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming . . . .

In case you were wondering how such laws applied to those were (already) mixed race, the Arizona Supreme Court seems to have opined that a person of mixed race (Caucasian) heritage could not marry anyone. State v. Pass, 59 Ariz. 16, 121 P.2d 882. (1942).

The Virginia statute was fairly typical in that it prohibited whites from marrying non whites, other than descendants of Pocahontas (no, really. I’m not making this up). The term “white person” was defined as referring “only to such person as has no trace whatever of any blood other than Caucasian; but persons who have one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed to be white persons.” Va. Code Ann. 20-54 (1960). The exception for persons with equal to or less than one-sixteenth “of the blood of the American Indian” is apparently accounted for, in the words of a tract issued by the Registrar of the State Bureau of Vital Statistics, by “the desire of all to recognize as an integral and honored part of the white race the descendants of John Rolfe and Pocahontas.” See, Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967).

In 1955, the Supreme Court of Virginia upheld that state’s “Racial Integrity Law” on the grounds that the State had a legitimate interest in “preserv[ing] the racial integrity of its citizens,” and preventing “the corruption of blood,” “a mongrel breed of citizens,” and “the obliteration of racial pride.” Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S.E.2d 749 (1955).

In 1967, in Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), the United States Supreme Court, in an opinion authored by Chief Justice Earl Warren (yes, the same Earl Warren), struck down all miscegenation laws as a violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In doing so, Justice Warren declared “marriage [to be] one of the basic civil rights of man” and which cannot be “restricted by invidious racial discriminations.”

Separate but Equal

West Coast Segregation

In addition to the land laws, discrimination against those of Japanese ancestry was quite common. The San Francisco Chronicle, for example, published articles such as “The Yellow Peril: How Japanese Crowd out the White Race.”

Such attitudes led to enforced segregation of whites and those of Japanese ancestry. Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the San Francisco school board, apparently to avoid “contaminating” white students, ordered children of Japanese descent, along with those of Chinese and Korean descent, segregated from white children. (The initial segregation ordinances were passed much earlier, but referred only to “Chinese and Mongolian,” and there apparently was some confusion as to whether Japanese comprise “Mongolians.”). Prior to the earthquake, children of Japanese descent studied in integrated schools.

Under pressure from President Theodore Roosevelt, the San Francisco school board withdrew its demand for segregation of Japanese children (in exchange, Roosevelt agreed to halt immigration from Japan pursuant to what is referred to as the “Gentleman’s Agreement”). Roosevelt’s intervention seems to have been geo-politically motivated. Just the previous year, he had brokered an end to the Russo-Japanese War, in which Japan had defeated the Russian navy. (Actually, the Japanese navy had struck first, in a surprise attack, to destroy the Russian Far East fleet. The Russians then sent their Baltic Sea fleet into the Atlantic, south around Africa, east past India, and into the Sea of Japan only to be promptly defeated at the Battle of Tsushima.). The war sent shock waves through the West and Roosevelt did not want to antagonize a militarily powerful Japan.

Segregation in the South

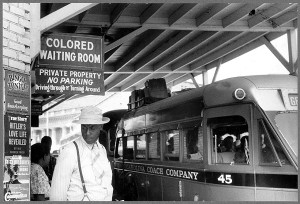

In 1896, in the now-infamous Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), the Supreme Court, following the lead of several state supreme courts (e.g., Massachusetts), endorsed the “separate but equal” doctrine, to the effect that equality of treatment is accorded when the “white” and “colored races” are provided substantially equal facilities even though these facilities be separate. See, Black’s Law Dictionary, Abr. 5th Ed., (West, 1983).

In 1896, in the now-infamous Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), the Supreme Court, following the lead of several state supreme courts (e.g., Massachusetts), endorsed the “separate but equal” doctrine, to the effect that equality of treatment is accorded when the “white” and “colored races” are provided substantially equal facilities even though these facilities be separate. See, Black’s Law Dictionary, Abr. 5th Ed., (West, 1983).

The statute at issue in Plessy was a Louisiana statute requiring separate accommodations for railway passengers, and specifically referred to the “white” and “colored” races. (The statutes in other states referred merely to “blacks” and “whites.”).

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Harlan alluded to the rather odd position of Asians in the the Jim Crow laws: “There is a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race. But, by the statute in question, a Chinaman can ride in the same passenger coach with white citizens of the United States, while citizens of the black race in Louisiana, many of whom, perhaps, risked their lives for the preservation of the Union, who are entitled, by law, to participate in the political control of the state and nation, who are not excluded, by law or by reason of their race, from public stations of any kind, and who have all the legal rights that belong to white citizens, are yet declared to be criminals, liable to imprisonment, if they ride in a public coach occupied by citizens of the white race.” Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)(Harlan, dissenting).

Almost thirty years later, the majority of the Court recognized this “error”, and announced that “the Mongolian or yellow race could not insist on being classed with the whites under this constitutional division [of white vs. colored].” Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927). At issue in Gong Lum were separate high schools for whites and coloreds.

Following Gong Lum, however, the Supreme Court began to reconsider the Jim Crow laws, and finally did away utterly with the “separate but equal” doctrine in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). At issue in Brown was the separation of white and Negro children in the Kansas public schools. The Court, per Chief Justice Warren, announced that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. [Non-whites] are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.”